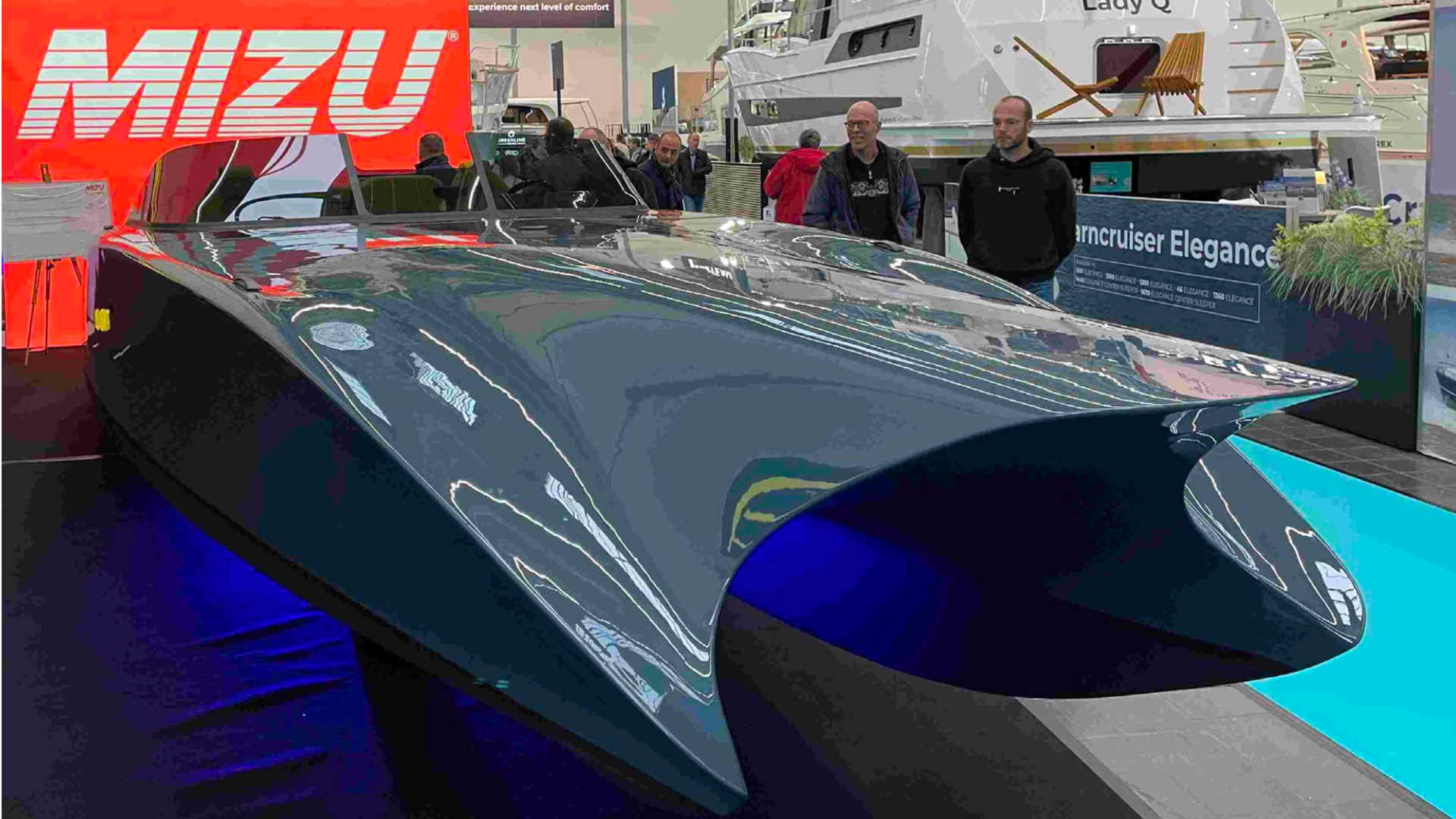

When you step aboard the Mira today, it’s hard to imagine the state she was once in. Built in 1953 for the American export market, she was a proud symbol of Dutch craftsmanship. Only one of her kind remained in the Netherlands and that very boat was found decades later in a dusty shed, weathered, forgotten, and almost beyond saving.

But the story didn’t end there. The original yard that once launched her decided to restore the vessel to her former glory. This time, however, they weren’t just looking backward. With the technology of today at hand, they saw an opportunity to marry tradition with innovation.

Why Electrify a Classic?

The Mira shows what true sustainability looks like. A well-built hull can outlast generations, often a century or more. What doesn’t last is the diesel engine bolted inside. Those clunky blocks of steel rarely survive more than a few decades before needing replacement.

That’s where the heart of sustainability lies: not only in propulsion, but in the sheer longevity of a ship. By electrifying the Mira, we wanted to show that even a vessel built more than seventy years ago can play its part in the transition towards cleaner waterways. A reminder that the future doesn’t always have to be newly built.

The System Behind the Mira

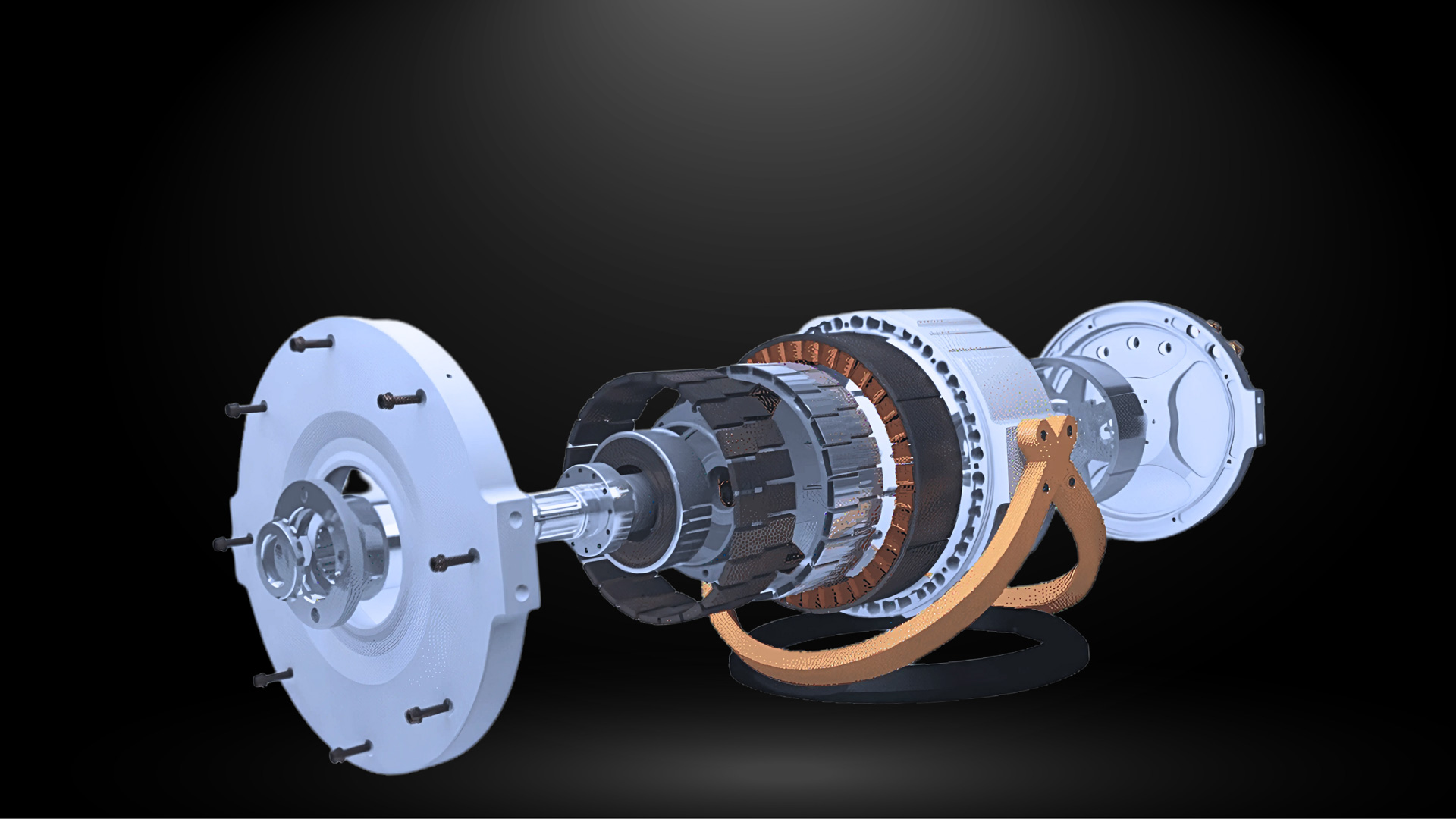

At the heart of the Mira lies a 60 kW electric motor, powered by a 75 kWh LiFePO4 battery bank. This gives her a fully electric range of up to 135 kilometers and a top speed of 13 knots.

We chose a system voltage of 358 V. That number wasn’t random. Higher voltages mean lower currents for the same power, which in turn reduces cable thickness, weight, and energy losses. Just as important, it lowers the risk of overheating in cables and connectors, one of the main causes of fire on board. By keeping current levels manageable, we prevent hotspots and make the system both safer and more reliable.

At the core of the propulsion system is the Power Distribution Unit (PDU), the central management hub of the drivetrain. It makes high-voltage operation safe and reliable by combining essential functions such as insulation monitoring, fuses, precharge circuits, and safety relays. The PDU also integrates a battery management system and uses HVIL (High Voltage Interlock Loop) connectors. HVIL makes it easier to install and work with high-voltage systems: if a connector is not fully engaged or comes loose, the PDU detects it instantly and shuts the system down. In practice, this means there is no way to accidentally touch high-voltage.

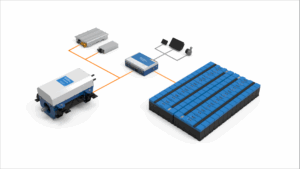

Charging is handled by a 22 kW fast charger, identical to what you’d find on electric cars and using the same plug standard. Importantly, this charger is bidirectional. That means the Mira can not only draw power from the grid, but also feed it back.

Today, charging infrastructure is often still a challenge, with many harbors limited by their grid connection. The Mira is prepared for vessel-to-grid, where her battery can act as a buffer to support the harbor network, or even as a home battery when connected at the owner’s house. This approach is something we are actively developing at STOK Electric, creating local energy networks and microgrids that make charging capacity more reliable and future-proof.

On board, we added a 2.8 kW bidirectional DC-DC converter. This allows the propulsion batteries to charge the service bank and vice versa. In practice, this means you can run all onboard systems, from cooking to navigation electronics, directly from the propulsion pack when needed. Or, when docked, you can use your standard shore charger to top up both propulsion and service systems seamlessly.

The Challenges Nobody Warns You About

Every conversion has its surprises, and the Mira was no exception. Unlike the automotive industry, there’s no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to boats. Especially not with classics. Space is limited, dimensions are irregular, and no two ships are ever the same.

Integration quickly became the greatest challenge. How do you keep a system as simple as possible, while also respecting the character of an old boat? There’s no room for a dozen separate boxes, extra filters, or spaghetti wiring. Everything had to be clean, compact, and intuitive.

One very concrete challenge we faced was electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). With higher voltages, the risk of electromagnetic interference increases. This can cause disruptions in navigation equipment, communication systems, or even other onboard electronics. To deal with this, we had to carefully design cable routing, use shielding where needed, and integrate an EMC filter into the system. It adds complexity, but it’s essential to ensure that the electric drivetrain doesn’t interfere with the rest of the vessel’s systems.

And once you step back, you realize the irony: what we call complicated today is still far simpler than the diesel engine it replaced. Rory Sutherland once framed it brilliantly when describing electric cars, and it applies perfectly to boats:

“Imagine if every boat were already electric. And then an engineer came along with a ‘better’ idea: storing hundreds of liters of highly flammable liquid on board, then burning it in a series of controlled explosions to create motion. It only works efficiently in a narrow RPM band, so you’ll also need a gearbox which needs oil. Add to that the filters, cooling systems, lubrication, constant maintenance and hundreds of moving parts. The result? More noise, vibration, fumes, and high upkeep.

And the one supposed advantage? Quick refueling — but only at specific stations, never conveniently at your dock or at home.”

For 95% of boat owners, that argument hits home. Unless you’re traveling 150 kilometers or more per day, electric propulsion is not just the greener choice, it’s the simpler, smarter one.

Did It Meet Expectations?

The shipyard team, many of them lifelong diesel mechanics, were skeptical at first. Their hands knew pistons and fuel lines better than cables and inverters. But as the system came together, their doubts faded. They began to see the elegance of simplicity.

Yes, working with the limited space was tricky. Yes, designing a system that fit without compromise took time. But the payoff was undeniable. On trials, the Mira achieved a silent cruising range of 135 kilometers on a single charge, with a top speed of 13 knots.

And perhaps more important than numbers: the feel. The hush of the water against the hull, the absence of vibration, the immediacy of torque when the throttle is eased forward. Those are the things that win hearts.

Lessons Learned Along the Way

Every project teaches you something new. From the Mira, a few lessons stand out:

- Integration is everything. The more seamless the system, the better the user experience. Keep it simple.

- Respect the boat’s DNA. Electrification shouldn’t overwrite a vessel’s history. In the Mira, we deliberately worked within the existing structure instead of forcing the layout around the system. That balance between heritage and technology is what keeps the boat authentic.

- Change requires patience. Skepticism is natural, especially from experienced diesel hands. The best way to win them over is through demonstration, not persuasion.

- Infrastructure matters. We often talk about batteries and motors, but charging capacity is equally crucial. Many marinas are limited by their grid connection, which makes large-scale charging a challenge. That’s why investing in the grid, and in smart local microgrids, is just as important as building better batteries and motors. The Mira’s 22 kW bidirectional charger is a small step in that direction, proving that a boat can not only charge from the grid but also give energy back when the harbor needs it, but the infrastructure is still far from where it needs to be.

The Bigger Picture

The Mira’s story isn’t just about one boat. It’s a case study in how heritage and sustainability can co-exist. It shows shipyards and owners alike that the electric transition isn’t reserved for futuristic designs, it’s also a way of breathing new life into vessels that already hold history in their planks.

And in that sense, the Mira is more than a boat. She’s proof that the future of boating can be as much about preservation as it is about progress.